Never Come Back Again Lyrics Austin Plain

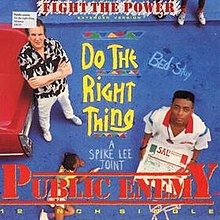

| "Fight the Power" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Unmarried past Public Enemy | ||||

| from the album Fright of a Black Planet and Practice the Right Thing: Original Motion Flick Soundtrack | ||||

| B-side | "Fight the Power (Flavor Flav Meets Fasten Lee)" | |||

| Released | July 4, 1989[1] | |||

| Recorded | 1989 | |||

| Genre | Political hip hop | |||

| Length | five:23 (soundtrack version) iv:42 (anthology version) | |||

| Label | Motown | |||

| Songwriter(s) |

| |||

| Producer(due south) | The Bomb Team | |||

| Public Enemy singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Fight the Power" on YouTube | ||||

"Fight the Power" is a vocal by American hip hop group Public Enemy, released as a single in the summer of 1989 on Motown Records. It was conceived at the request of film director Spike Lee, who sought a musical theme for his 1989 picture show Practice the Right Thing. First issued on the movie's 1989 soundtrack, a different version was featured on Public Enemy'due south 1990 studio album Fear of a Black Planet.

"Fight the Power" incorporates various samples and allusions to African-American culture, including civil rights exhortations, black church building services, and the music of James Dark-brown.

As a single, "Fight the Power" reached number one on Hot Rap Singles and number xx on the Hot R&B Singles. It was named the best single of 1989 by The Village Voice in their Pazz & Jop critics' poll. It has become Public Enemy's best-known song and has received accolades as one of the greatest songs of all time past critics and publications. In 2001, the song was ranked number 288 in the "Songs of the Century" listing compiled by the Recording Industry Association of America and the National Endowment for the Arts. In 2021, the song was ranked number two in Rolling Rock 'southward 500 Greatest Songs of All Time list.

Background [edit]

In 1988, shortly afterward the release of their second album It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, Public Enemy were preparing for the European leg of the Run's House bout with Run–D.M.C.[2] Before embarking on the tour, film managing director Spike Lee approached Public Enemy with the proposition of making a vocal for one of his movies.[2] Lee, who was directing Practise the Correct Affair, sought to use the song as a leitmotif in the film well-nigh racial tension in a Brooklyn, New York neighborhood.[three] He said of his decision in a subsequent interview for Time, "I wanted it to be defiant, I wanted it to exist angry, I wanted it to be very rhythmic. I thought right abroad of Public Enemy".[4] At a meeting in Lower Manhattan, Lee told lead MC Chuck D, producer Hank Shocklee of the Bomb Squad, and executive producer Bill Stephney that he needed an anthemic song for the film.[5]

While flying over Italy on the bout, Chuck D was inspired to write nigh of the song.[5] He recalled his idea, "I wanted to take sorta similar the same theme as the original 'Fight the Power' by The Isley Brothers and fill it in with some kind of modernist views of what our environment were at that particular fourth dimension."[5] The group's bass player Brian Hardgroove has said of the vocal'southward message, "Constabulary enforcement is necessary. Equally a species we haven't evolved past needing that. Fight the Ability is not about fighting say-so—it'due south not that at all. It'southward well-nigh fighting corruption of power."[half-dozen]

Recording and production [edit]

Branford Marsalis (photographed in 2011) played a saxophone solo for the vocal's soundtrack version.

The Bomb Team, Public Enemy's product team, constructed the music for "Fight the Power", through the looping, layering, and transfiguring of numerous samples.[7] The rails features but 2 live instrumentalists: saxophone, played by Branford Marsalis, and scratches provided by Terminator 10, the group's DJ and turntabilist[vii]—Marsalis likewise played a saxophone solo for the extended soundtrack version of the vocal.[8]

In dissimilarity to Marsalis' school of idea, Bomb Squad members such as Hank Shocklee wanted to eschew melodic clarity and harmonic coherence in favor of a specific mood in the composition. Shocklee explained that their musicianship was dependent on unlike tools, exercised in a different medium, and was inspired by different cultural priorities, different from the "virtuosity" valued in jazz and classical music.[9] Marsalis afterwards remarked on the group's unconventional musicality:

They're not musicians, and don't claim to be—which makes it easier to exist around them. Like, the song's in A minor or something, and so information technology goes to D7, and I call back, if I remember, they put some of the A pocket-size solo on the D7, or some of the D7 stuff on the A minor chord at the finish. So information technology sounds actually different. And the more unconventional it sounds, the more they like it.[nine]

Equally with other Public Enemy songs, the Bomb Squad recontextualized various samples, and used them to complement the vocals and mood of "Fight the Power".[9] The percussive sounds were placed either alee of or behind the beat, to create a feeling of either easiness or tension.[9] Particular elements, such as Marsalis' solo, were reworked past Shocklee so that they would signify something dissimilar from harmonic coherence.[nine] The Bomb Squad layered parts of Marsalis' D minor improvisations over the song's B♭7 groove, and vice versa.[9] Regarding the production of the song, Robert Walser, an American musicologist, wrote that the solo "has been advisedly reworked into something that Marsalis would never think to play, because Schocklee's goals and bounds are different from his."[9]

On August 24, 2014, Chuck D posted a photo on his Twitter contour of a cassette tape from the Green St. studio. The tape's label is branded with the studio's branding and a hand-written title suggests that the studio was used for the recording of the song.[10]

Sampling and loops [edit]

Although it samples many dissimilar works, the total length of each sample fragment is fairly short, equally nigh bridge less than a 2d, and the primary technique used to construct them into the track was looping past Flop Squad-producers Hank and Keith Shocklee.[11] In looping, a recorded passage—typically an instrumental solo or intermission—could be repeated past switching dorsum and forth between ii turntables playing the same record. The looping in "Fight the Power", and hip hop music in general, directly arose from the hip hop DJs of the 1970s, and both Shocklees began their careers every bit DJs.[11] Although the looping for "Fight the Power" was not created on turntables, it has a central connection to DJing. Author Marking Katz writes in his Capturing Audio: How Technology Has Changed Music, "Many hip-hop producers were once DJs, and skill in selecting and assembling beats is required of both. ... Moreover, the DJ is a primal, founding figure in hip-hop music and a abiding point of reference in its discourse; producers who stray as well far from the practices and aesthetics of DJing may risk compromising their hip-hop credentials".[eleven]

Chuck D recalled the rail'south extravagant looping and production, saying that "nosotros put loops on top of loops on top of loops".[xi] Katz comments in an assay of the rail, "The effect created by Public Enemy'due south production team is dizzying, exhilarating, and tantalizing—conspicuously one cannot take it all in at one time".[11] He continues by discussing the connectedness of the production to the work as a whole, stating:

When Public Enemy'southward rapper and spokesman Chuck D. explains, "Our music is all about samples," he reveals the axis of recording technology to the group's work. Only put, "Fight the Power," and likely Public Enemy itself, could not exist without it. "Fight the Power" is a complex and subtle testament to the influence and possibilities of sound recording; just at the same time, information technology reveals how the aesthetic, cultural, and political priorities of musicians shape how the engineering is understood and used. A look at Public Enemy'southward use of looping and performative quotation in "Fight the Power" illuminates the mutual influences betwixt musician and automobile.[11]

Limerick [edit]

Musical structure [edit]

"Fight the Power" begins with a vocal sample of civil rights attorney and activist Thomas "TNT" Todd, speechifying in a resonant, agitated voice, "Withal our best trained, best educated, best equipped, best prepared troops refuse to fight. Matter of fact, information technology'southward prophylactic to say that they would rather switch than fight".[7] This xvi-2d passage is the longest of the numerous samples incorporated to the track.[7] It is followed by a cursory three-mensurate section (0:17–0:24) that is carried by the dotted rhythm of a song sample repeated six times; the line "pump me up" from Trouble Funk's 1982 song of the same proper name played backwards indistinctly.[7] The rhythmic measure-section also features a melodic line, Branford Marsalis' saxophone playing in triplets that is buried in the mix, eight snare drum hits in the second measure, and vocal exclamations in the third mensurate.[7] One of the exclamations, a nonsemantic "chuck chuck" taken from the 1972 song "Whatcha See Is Whatcha Get" by The Dramatics, serves as a reference to Chuck D.[7]

The three-measure out section crescendos into the following section (0:24–0:44), which leads to the entrance of the rappers and features more complex production.[xi] [12] In the first four seconds of the section, no less than 10 distinct samples are looped into a whole texture, which is then repeated 4 more times as a meta-loop.[11] The whole section contains samples of guitar, synthesizer, bass, including that of James Brown's 1971 recording "Hot Pants", four fragmented song samples, including those of Brown'southward famous grunts in his recordings, and various percussion samples.[eleven] Although it is obscured by the other samples, Clyde Stubblefield's pulsate break from James Brown's 1970 vocal "Funky Drummer", one of the most frequently sampled rhythmic breaks in hip hop,[13] makes an appearance, with only the break's first 2 eighth notes in the bass drum and the snare hit in clarity.[eleven] This section has a sharp, funky guitar riff playing over staccato rhythms, as a class voice exhorts the line "Come on, become downwardly".[12] Other samples include "I Know You Got Soul", "Planet Rock" and "Teddy'due south Jam".

Lyrics [edit]

The song's lyrics features revolutionary rhetoric calling to fight the "powers that exist".[3] They are delivered by Chuck D, who raps in a confrontational, unapologetic tone.[12] David Stubbs of The Quietus writes that the song "shimmies and seethes with all the controlled, incendiary rage and intent of Public Enemy at their height. It'south gear up in the firsthand futurity tense, a condition of permanently impending insurrection".[xiv]

"Fight the Power" opens with Chuck D roaring "1989!"[fourteen] His lyrics declare an African-American perspective in the first verse, equally he addresses the "brothers and sisters" who are "swingin' while I'm singin' / Givin' whatcha gettin'".[12] He also clarifies his group's platform equally a musical artist: "At present that you've realized the pride'south arrived / We've got to pump the stuff to make the states tough / From the heart / It's a outset, a work of fine art / To revolutionize".[15] In addressing race, the lyrics dismiss the liberal notion of racial equality and the dynamic of transcending i's circumstances every bit it pertains to his group of people: "'People, people we are the same' / No, we're non the aforementioned / 'Cause we don't know the game".[12] [sixteen] Chuck D goes on to telephone call from the power structure to "requite us what we desire/ Gotta requite usa what nosotros need", and intelligent activism and organization from his African-American community: "What we need is awareness / Nosotros tin't get careless ... Let'south become down to business / Mental cocky-defensive fitness".[12] In the line, Chuck D references his audience as "my beloved", an allusion to Martin Luther King Jr.'s vision of the "beloved customs".[15]

The samples incorporated to "Fight the Power" largely draw from African-American civilisation, with their original recording artists beingness mostly important figures in the development of late 20th-century African-American pop music.[17] Vocal elements characteristic of this are various exhortations common in African-American music and church building services, including the lines "Permit me hear you say", "Come on and get down", and "Brothers and sisters", as well as James Brownish's grunts and Afrika Bambaataa's electronically candy exclamations, taken from his 1982 vocal "Planet Rock".[17] The samples are reinforced by textual allusions to such music, quoted by Chuck D in his lyrics, including "audio of the funky drummer" (James Brown and Clyde Stubblefield), "I know you got soul" (Bobby Byrd), "freedom or decease" (Stetsasonic), "people, people" (Brown's "Funky President"), and "I'thou black and I'm proud" (Brownish'due south "Say It Loud – I'thou Blackness and I'k Proud").[17] The track's title itself invokes the Isley Brothers' song of the same name.[17]

Third poetry [edit]

The song'south third verse contains disparaging lyrics about iconic American entertainers Elvis Presley and John Wayne,[18] equally Chuck D raps, "Elvis was a hero to most / But he never meant shit to me / Direct up racist, the sucker was / Unproblematic and plain", with Flavour Flav following, "Fuck him AND John Wayne!".[19] Chuck D was inspired to write the lines afterward hearing proto-rap creative person Clarence "Blowfly" Reid'due south "Blowfly Rapp" (1980), in which Reid engages in a battle of insults with a fictitious Klansman who makes a similarly phrased, racist insult against him and boxer Muhammad Ali.[19]

The third verse expresses the identification of Presley with racism—either personally or symbolically—and the fact that Presley, whose musical and visual performances owed much to African-American sources, unfairly accomplished the cultural acknowledgment and commercial success largely denied to his blackness peers in rock and coil.[eighteen] [20]

Chuck D later clarified his lyric associating Elvis Presley with racism. In an interview with Newsday timed with the 25th ceremony of Presley's decease, Chuck D best-selling that Elvis was held in high esteem by black musicians, and that Elvis himself admired blackness musical performers. Chuck D stated that the target of his line about Elvis was the white civilization which hailed Elvis as a "King" without acknowledging the black artists that came before him.[21] [22]

The line disparaging John Wayne is a reference to his controversial personal views, including racist remarks made in his 1971 interview for Playboy, in which Wayne stated, "I believe in white supremacy until the blacks are educated to a point of responsibleness. I don't believe in giving authority and positions of leadership and judgment to irresponsible people."[18]

Chuck D clarifies previous remarks in the verse's subsequent lines: "Cause I'thousand black and I'one thousand proud / I'm ready and hyped, plus I'm amped / Near of my heroes don't appear on no stamps / Sample a look back you look and find / Naught but rednecks for 400 years if you check".[12] [sixteen] Laura Thousand. Warrell of Salon interprets the poesy as an attack on embodiments of the white American ideal in Presley and Wayne, likewise as its discriminative civilization.[12]

Release and reception [edit]

On May 22, 1989, Professor Griff, the group's "Minister of Data", was interviewed by The Washington Times and made anti-Semitic comments, calling Jews "wicked" and blaming them for "the majority of wickedness that goes on across the globe", including financing the Atlantic slave trade and beingness responsible for South African apartheid.[23] The comments drew attention from the Jewish Defense Organization (JDO), which announced a boycott of Public Enemy and publicized the issue to tape executives and retailers.[23] Consequently, the song's inclusion in Do the Correct Affair led to pickets at the film'south screenings from the JDO.[24] Griff's interview was also decried by media outlets.[25] In response, Chuck D sent mixed letters to the media for a month, including reports of the group disbanding, not disbanding, boycotting the music industry, and dismissing Griff from the group.[23] In June, Griff was dismissed from the group,[25] and "Fight the Power" was released on a one-off bargain with Motown Records.[26] Public Enemy subsequently went on a cocky-imposed interruption from the public in lodge to take pressure off of Lee and his picture.[25] Their next single for Fear of a Blackness Planet, "Welcome to the Terrordome", featured lyrics defending the group and attacking their critics during the controversy, and stirred more controversy for them over race and antisemitism.[27]

During their self-imposed inactivity, "Fight the Power" climbed the Billboard charts.[25] Information technology was released as a 7-inch single in the U.s.a. and the United Kingdom, while the song's extended soundtrack version was released on a 12-inch and a CD maxi single.[26]

"Fight the Power" was well-received past music critics upon its release. Greg Sandow of Amusement Weekly wrote that it is "possibly the strongest popular single of 1989".[28] "Fight the Power" was voted the all-time unmarried of 1989 in The Village Vocalization 's annual Pazz & Jop critics' poll.[29] Robert Christgau, the poll'southward creator, ranked it equally the sixth best on his own list.[30] It was nominated for a Grammy Accolade for Best Rap Performance at the 1990 Grammy Awards.[31]

The lyrics disparaging Elvis Presley and John Wayne were shocking and offensive to many listeners at the time.[19] Chuck D reflected on the controversy surrounding these lyrics by stating that "I think it was the first time that every word in a rap vocal was beingness scrutinized word for discussion, and line for line."[32]

Music video [edit]

The song's music video was filmed in Brooklyn on April 22, 1989,[1] and presented Public Enemy in office political rally, part live performance.[33] Public Enemy biographer Russell Myrie wrote that the video "accurately [brought] to life ... the emotion and anger of a political rally".[34]

Fasten Lee produced and directed 2 music videos for this song. The commencement featured clips of various scenes from Do the Right Affair.[35] In the 2d video, Lee opened the video with moving-picture show from the 1963 March on Washington and transitioned to a staged, massive political rally in Brooklyn called the "Young People's March to Cease Racial Violence".[36] Extras wearing T-shirts that said "Fight the Ability" carried signs featuring Paul Robeson, Marcus Garvey, Angela Davis, Frederick Douglass, Muhammad Ali, and other black icons.[36] Others carry signs resembling the signs used to designate state delegations at a national political convention. Tawana Brawley fabricated a cameo appearance. Brawley gained national notoriety in 1987 when, at the age of 15, she accused several police officers and public officials from Wappingers Falls, New York of raping her. The accuse was rejected in court, and she instead was sued for supposedly fabricating her story. Jermaine Dupri likewise made a cameo.[ citation needed ]

Appearances [edit]

"Fight the Power" plays through Spike Lee's film Do the Right Thing. It plays in the opening credits as Rosie Perez's graphic symbol Tina dances to the song, shadowboxing and demonstrating her personality's animus.[37] [38] The song is nearly prevalent in scenes with Bill Nunn's imposing character Radio Raheem, who carries a boombox around the film'southward neighborhood with the song playing loudly and represents Blackness consciousness.[39]

Additionally, "Fight the Power" was also featured in the opening credits of the PBS documentary Style Wars about inner-metropolis youth using graffiti as an artistic course of social resistance.[40] [ better source needed ]

In 1989, "Fight the Power" was played in the streets of Overtown, Miami, in celebration of the guilty verdict of police officeholder William Lozano, whose shooting of a black motorist led to two fatalities and a three-twenty-four hours riot in Miami that heightened tensions between African Americans and Hispanics.[41] That year, the song was also played at the African-American fraternity party Greekfest in Virginia Embankment, where tensions had grown betwixt a predominantly White police forcefulness and festival-attending African Americans. According to attendees, the Greekfest riots were precipitated by a frenzied oversupply that had heard the song as it was played from a black van.[42]

"Fight the Ability" also appears in the films Jarhead (2005), Cloudy with a Adventure of Meatballs (2009) and Star Expedition Beyond (2016).

Legacy and influence [edit]

Public Enemy's explosive 1989 striking single brought hip-hop to the mainstream—and brought revolutionary acrimony back to popular.

— Laura K. Warrell, Salon [12]

"Fight the Power" became an anthemic song for politicized youth when it was released in 1989.[43] Janice C. Simpson of Time wrote in a 1990 commodity, "The song not only whipped the movie to a peppery pitch just sold well-nigh 500,000 singles and became an anthem for millions of youths, many of them black and living in inner-metropolis ghetto's [sic]."[4] Laura K. Warrell of Salon writes that the song was released "at a crucial menses in America's struggle with race", crediting the song with "capturing both the psychological and social conflicts of the time."[12] She interprets it as a reaction to "the frustrations of the Me Decade", including the crack epidemic in the inner cities, AIDS pandemic, racism, and the furnishings of Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush-league's presidencies on struggling urban communities.[12] Warrell cites "Fight the Power" as Public Enemy's "most attainable hit", noting its "uncompromising cultural critique, its invigoratingly danceable sound and its rallying", and comments that it "acted as the perfect summation of [the group's] ideology and audio."[12] It became Public Enemy'due south best-known song amongst music listeners.[two] The grouping closes all their concerts with the song.[two] [32] Spike Lee and the group collaborated again in 1998 on the soundtrack album to Lee's film He Got Game, also the grouping'south 6th studio anthology.[44]

Chuck D acknowledged that "Fight the Ability" is "the nearly important record that Public Enemy take done". [32] Critics and publications accept also praised "Fight the Power" as i of the greatest songs of all time.[45] In 2001, the song was ranked number 288 in the "Songs of the Century" list compiled by the Recording Industry Clan of America and the National Endowment for the Arts.[46] In 2004, it was ranked number 40 on AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs, a list of the top 100 songs in American cinema.[47] In 2004, Rolling Rock ranked the song number 322 on its list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.[48] The vocal was ranked number 2 in Rolling Stone 'southward 2021 listing.[49] In 2008, it was ranked number one on VH1's 100 Greatest Songs of Hip Hop.[50] In 2011, Time included the vocal on its listing of the All-Fourth dimension 100 Songs.[51] "Fight the Power" is also 1 of The Stone and Whorl Hall of Fame'southward 500 Songs that Shaped Stone and Roll.[52] In September 2011 it topped Time Out 's list of the 100 Songs That Changed History, with Matthew Collin, author of This Is Serbia Calling, citing its use by the rebel radio station B92 during the 1991 protests in Belgrade equally the reason for its inclusion. Collin explained that, when B92 were banned from broadcasting news of the protests on their station, they circumvented the ban by instead playing "Fight the Ability" on heavy rotation to motivate the protestors.[53]

Cover versions [edit]

In 1996, the vocal was covered past D.C.K. for the electro-industrial various artists compilation Functioning Beatbox.[54]

In 1993, the song was covered by Barenaked Ladies for the Coneheads motion-picture show soundtrack.[55]

In 2011, American mathcore band The Dillinger Escape Programme covered the song with Chuck D. on the album Homefront: Songs for the Resistance; a promo for the video game Homefront. [56]

In July 2020, Public Enemy did a live performance of "Fight the Power" at the 2020 BET Awards, alongside YG, Nas, Black Thought, and Rapsody, among others.[57]

Charts [edit]

Certifications [edit]

References [edit]

- ^ a b "In the Summertime of 1989 "Fight the Power" Saved Public Enemy & Almost Sank 'Do the Correct Matter'". Okayplayer. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Myrie (2008), p. 121.

- ^ a b Watrous, Peter (April 22, 1990). "Recordings; Public Enemy Makes Waves - and Compelling Music". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved June vii, 2012.

- ^ a b Simpson, Janice C. (February 5, 1990). "Music: Yo! Rap Gets on the Map". Time. Vol. 135. New York. p. lx. Retrieved June seven, 2018.

- ^ a b c Myrie (2008), p. 122.

- ^ "The Best Rap Vocal, Every Year Since 1979". Complex. July eight, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Katz (2004), p. 160.

- ^ Mueller, Darren (January 16, 2012). "Listening Session with Branford Marsalis". Marsalis Music. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f m Walser et al. Austin & Willard (1998), 297.

- ^ Chuck D [@MrChuckD] (August 24, 2014). "Vintage sht. FTP" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b c d e f grand h i j Katz (2004), p. 161.

- ^ a b c d e f chiliad h i j g l Warrell, Laura K. (June 3, 2002). "Fight the Power". Salon . Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Kun, Josh: "What Is an MC If He Can't Rap to Banda? Making Music in Nuevo L.A." American Quarterly (American Studies Assn) (Baltimore, Dr.) (56:3) September 2004, 741-758. (2004)

- ^ a b Stubbs, David (April 12, 2010). "xx Years On: Remembering Public Enemy's Fear Of A Black Planet". The Quietus. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Friskics-Warren (2006), p. 183.

- ^ a b Friskics-Warren (2006), p. 182.

- ^ a b c d Katz (2004), p. 163.

- ^ a b c Myrie (2008), p. 124.

- ^ a b c Myrie (2008), p. 123.

- ^ Pilgrim, David (March 2006). "Question of the Month: Elvis Presley and Racism". Jim Crow Museum at Feris State Academy. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

- ^ "Chuck Hails the King". The Age. August 13, 2002. Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- ^ Ed Masley (July 4, 2004). "Elvis may have been the king, merely was he outset". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette . Retrieved May viii, 2014.

- ^ a b c Santoro (1995), p. 119.

- ^ Screen. Oxford University Press. 31: 36. 1990 https://academic.oup.com/screen/article-abstract/31/1/26/1676221?redirectedFrom=PDF.

- ^ a b c d Santoro (1995), p. 120.

- ^ a b Strong (2004), p. 1226.

- ^ Santoro (1995), p. 121.

- ^ Sandow, Greg (April 27, 1990). "Fearfulness of a Blackness Planet Review". Entertainment Weekly . Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Staff (February 27, 1990). Robert Christgau: Pazz & Jop 1989: Critics Poll. The Village Voice. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (February 27, 1990). "Pazz & Jop 1989: Dean'due south List". The Village Voice . Retrieved July viii, 2013.

- ^ DeKnock, Jan (February 16, 1990). "Who'll Win The Grammys?". Chicago Tribune . Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c Chuck D remembers 'Black Planet' . Interviewed by Gail Mitchell. Billboard. March 2010.

- ^ Myrie (2008), p. 125.

- ^ Myrie (2008), p. 169.

- ^ Barlow, Aaron (August 11, 2014). Star Power: The Bear on of Branded Celebrity [2 volumes]: The Touch of Branded Celebrity [two volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN9780313396182 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Chang, Jeff (2005). Can't Terminate Won't Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. New York: Picador. pp. 279–280, 286. ISBN0312425791.

- ^ The San Francisco Jung Institute Library Journal. Virginia Allan Detloff Library of the C.K. Jung Institute. nine: 85. 1989.

- ^ Nordic Association for American Studies (1989). American Studies in Scandinavia. Universitetsforlaget (21–22): 110.

- ^ "Les Nerfs a Fleur de Peau". Afrique (in French). Groupe Jeune Afrique (57–65): 6. 1989.

- ^ Silver, Tony (January one, 2000), Style Wars , retrieved December 14, 2016

- ^ Newsweek. Vol. 114, no. 19–27. p. 136.

- ^ Campbell, Roy H. (September 10, 1989). "Why Virginia Embankment Happened". The Philadelphia Inquirer . Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ Washington University (Saint Louis, Mo.). Dept. of Sociology, State University of New York at Buffalo. Graduate Philosophy Association (1990). Telos. Department of Sociology, Washington University: 178. CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Myrie (2008), p. 204.

- ^ "Fight the Power". Acclaimed Music. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ "Songs of the Century". CNN. March 7, 2001. Archived from the original on Dec 11, 2005. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs. American Film Found. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone (963). Dec nine, 2004. Archived from the original on June 21, 2008. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Fourth dimension". Rolling Rock. September 15, 2021. Retrieved Oct vi, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ 100 Greatest Hip Hop Songs. VH1. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ "All-Time 100 Songs". Fourth dimension. October 24, 2011. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ 500 Songs Archived May 2, 2007, at the Wayback Automobile. The Rock and Whorl Hall of Fame. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ "100 Songs That Changed History". Time Out. London. September 2011. Archived from the original on September 23, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ Christian, Chris (Baronial 1996). "Various Artists: Operation Beatbox". Sonic Boom. 4 (7). Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ Knott, Robert; Penner, Jonathan; Hubley, Whip; Aykroyd, Dan (July 23, 1993), Coneheads , retrieved January 31, 2017

- ^ "An Album Of Metallic Covers For My Electronic mail Address? DEAL! - Metal Injection". March 22, 2011.

- ^ Bloom, Madison (July 10, 2020). "YG Dresses as Colin Kaepernick in Video for New Song 'Swag'". Pitchfork . Retrieved July eleven, 2020.

- ^ "Nederlandse Top 40 – calendar week 34, 1989" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Visitor. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ a b "Public Enemy – Awards". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved June xv, 2013.

- ^ "Public Enemy Nautical chart History (Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved June xv, 2013.

- ^ "American video certifications – Public Enemy – Fight the Power Live". Recording Industry Association of America.

Bibliography [edit]

- Austin, Joe; Willard, Michael, eds. (1998). Generations of Youth: Youth Cultures and History in Twentieth-Century America . NYU Press. p. 297. ISBN0-8147-0646-0.

- Friskics-Warren, Bill (September i, 2006). I'll Take You In that location: Pop Music and the Urge for Transcendence . London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN0826419216.

- Katz, Mark (2004). Capturing Audio: How Engineering Has Changed Music . University of California Printing. ISBN0-520-24380-iii.

- Santoro, Gene (October 12, 1995). Dancing in Your Caput: Jazz, Blues, Rock, and Beyond . Oxford University Press. ISBN0195101235.

- Strong, Martin Charles (Oct 21, 2004). The Not bad Rock Discography (seventh ed.). Canongate U.South. ISBN1841956155.

External links [edit]

- "Fight the Power" at Discogs

- Fasten's Anarchism — Mother Jones

- [1] NPR feature on 1975's "Fight the Power" past The Isley Brothers and how that inspired Public Enemy's "Fight the Power"

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fight_the_Power_(Public_Enemy_song)

0 Response to "Never Come Back Again Lyrics Austin Plain"

Post a Comment